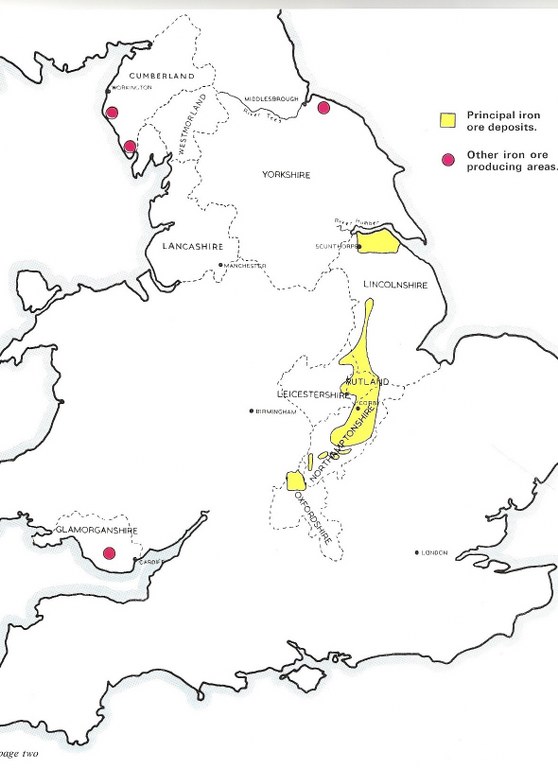

A Brief History of Iron Ore Mining and Production in Rutland and the East Midlands

Ironstone is a naturally occurring rock which contains minerals, notably iron. Ironstone was formed due to sedimentation on ancient sea beds during the Jurassic period in geological history, some 145 million years ago. Eventually, as the seas over Britain receded, and millions of years passed by, these deposits formed three distinct types of iron ore. Locally the important ironstone is called “Northampton Sand” ironstone which forms part of the escarpment in almost a continuous line which stretches from the River Humber to near Corby. This was associated with the overlying deposit of Lincolnshire Limestone together forming the geological feature known as Lincoln Edge on which stand the well-known landmarks of Lincoln Cathedral and Rockingham Castle.

Another type of ironstone known as “Marlstone” appears as outcrops at Caythorpe in Lincolnshire, locally at Woolsthorpe by Belvoir and also near Banbury in north Oxfordshire.

In Roman times there was much iron making in the area as outcrops of ironstone rock were exploited for smelting. Although generally less well known, medieval ore extraction continued for many centuries and only reached its peak in the 17th Century as evidenced by the building of Rockingham Castle to protect the Royal forges. Unfortunately, the local industry was to founder when higher-grade imports of ore from Sweden were introduced.

During the early years of the industrial revolution, the ores of the East Midlands were virtually forgotten as ironworks sprang up in coal and limited ironstone producing areas such as South Wales, Cumbria and Teeside. It was only when these sources of ironstone began to be worked out that serious consideration was given to alternative sources of ironstone supply. Samples of local iron ores were shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851 with these inspiring investment in a new ironworks in the Wellingborough area. Most home-produced ores at this time contained too much phosphorus for steel production and imports were still required. In 1879 however, the Gilchrist Thomas patented method allowed home ore to be used for steel making thus allowing the extensive East Midlands ironstone field to be developed.

East Midlands ore field in UK context

In Rutland the construction of the Midland Railway through the County opened up the prospect of new ironstone workings along the escarpment near Cottesmore. The construction of the two-mile Midland Railway Ashwell to Cottesmore mineral branch from the Oakham to Melton Mowbray railway in 1884 was inspired by iron ore workings that had started by the Sheepbridge Coal and Iron Company in 1882 at the top of the escarpment.

Diorama of Cottesmore hand working

Whilst initially quarry extraction involved hand working with the use of horse and carts to take the ironstone to the railway station at Ashwell a three-foot gauge tramway rail transport system was built to serve the ironstone quarries on top of the escarpment and a rope worked incline allowed fully loaded wagons to be lowered down the steep slope of the eastern edge of the Vale of Catmose to then tip the ironstone into the mainline rail wagons for onward transport to the steelworks. At this time such transport methods were considered to be “cutting edge”, being replicated at a number of other quarries in the ironstone field.

Diorama of Cottesmore loco and digger.

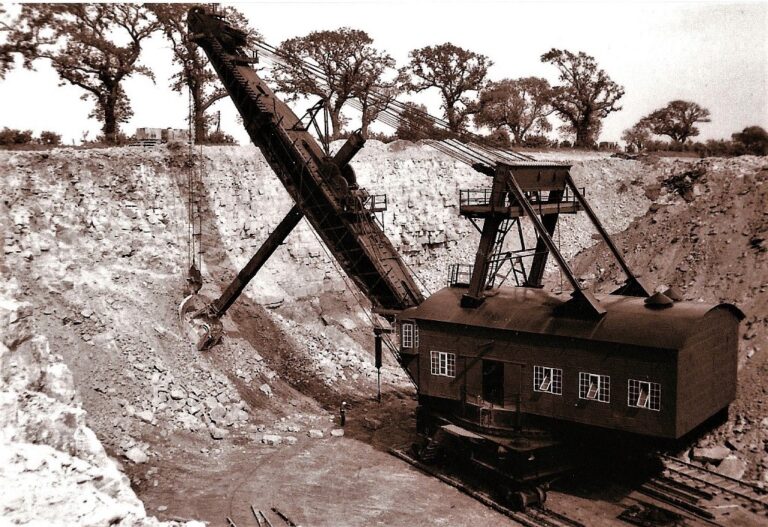

The ironstone seam that outcrops along the top of the escarpment dips steadily towards the east under increasing depths of cover (known as overburden). Consequently to exploit the ore fields further from its outcrop, greater investment was required in the form of new and heavier machinery (face shovels and draglines) and extensions to the quarry railways.

A new ironstone quarry was opened up near the village of Market Overton in 1906 by James Pain Ltd who sold ironstone on the open market. A new rail link to the Saxby- Bourne railway was built and the quarry workings served by a standard gauge tramway. Pain’s quarries were taken over by the Stanton Ironworks Company in 1928 who were in turn acquired by Stewarts and Lloyds Minerals in 1950. The quarries were expanded in the 1950’s when the arrival of a large stripping shovel allowed extraction to be undertaken from areas having deeper overburden.

Photo of R&R 5360 digging overburden at Market Overton.

James Pain Ltd further extended his ironstone quarrying interests in 1912 by opening up a new quarry near Uppingham. During the First World War a second quarry face was opened up in response to increased demand and german prisoners of war worked in the quarries to aid production. Demand fell sharply after the cessation of hostilities leading ultimately to quarry closure in 1926.

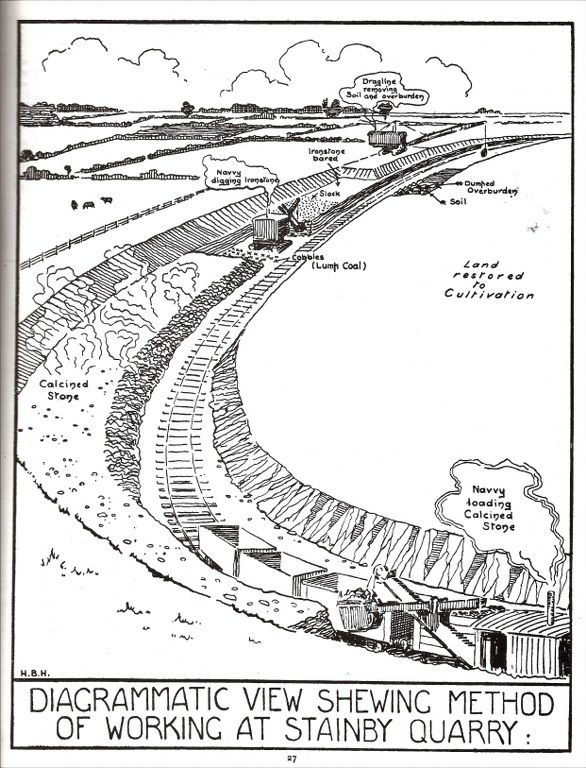

Looking for new ironstone resources to replace their dwindling availability in Cleveland, Bell Brothers Ltd (later to be taken over by Dorman Long) opened up ironstone quarries near Burley in Rutland in 1919, which also connected to the Cottesmore Mineral Branch. These employed steam powered quarry excavators from the outset and the initial narrow gauge railway was soon replaced by a standard gauge line in 1926 avoiding the need to tranship the ironstone to mainline wagons. In marked contrast to the workings at nearby Cottesmore much of the ironstone extracted was part smelted at the quarry by a process of calcining. This involved creating large clamps of ironstone, either at the quarry face (e.g. Stainby Quarry) or nearby land ,which was mixed with coal slack and then set alight. The resultant fires burned for weeks to drive off moisture and any volatiles before the purple coloured calcined ore was loaded into rail wagons for the long journey to the steelworks located on Teeside.

Shewing method of working at Stainby

The year 1919 proved to be a busy year for the expansion of ironstone quarrying in the County as the Staveley Coal and Iron Co. Ltd opened up a new ironstone quarry near the village of Pilton. Again steam operated excavators were used from the outset and the quarry was significantly expanded over the years to three pits, all of which were required to produce ironstone to meet wartime needs in World War 2.

The Kettering Iron and Coal Company (trading as the Luffenham Iron Ore Co.Ltd ) also sought to open up a new quarry at Luffenham in 1919 but they were primarily interested in securing new resources of limestone and only very modest quantities of ironstone were ever produced until cessation of ironstone production in 1925.

During World War 2 a small ironstone quarry was opened up at Barrowden by the Nassington Barrowden Mining Co Ltd but these workings only lasted until 1948.

After the Second World War there was an urgent need to re-build a war-ravaged Britain and huge capital investment was required from the United Steels Companies Ore Mining Branch from 1950 to exploit the extensive ironstone deposits at Exton Park in Rutland. The extensive quarry railway system connected to the Cottesmore Branch with the tracks encircling the village of Exton. Here, the overburden varied between 60 – 100 feet in depth and exploitation required the introduction of large electrically powered quarry excavators including the famous “Sundew”, a monster 1675 ton W1400 walking dragline built by Ransomes & Rapier of Ipswich. Constructed in 1957 it was, at the time, the largest walking dragline in the world.

In the local area, the increasing depths of overburden led both United Steel Companies and Stewarts Lloyds Ltd to develop underground mining as an alternative to opencast working. Mines at Easton and Thistleton were opened up in the mid 1950’s but ultimately failed due to problems associated with geological difficulties, high development cost and water ingress.

Narrow gauge electric quarry train at Thistleton Mine

Areas lying adjacent to Rutland both to the north and south have seen extensive mineral workings for ironstone. To the north in South Lincolnshire the construction of the High Dyke mineral branchline in 1916 allowed the development of extensive ironstone quarries around Buckminster, Stainby, Sproxton and Colsterworth whilst a new ironstone quarry at Harlaxton near Grantham was opened up during the Second World War to supplement production from other older ironstone quarries in the Vale of Belvoir.

To the south could be found a series of ironstone quarry workings in Northamptonshire at Cranford, Storefield, Irchester, Irthlingborough, Glendon, Blisworth, Desborough, Nassington and Wellingborough whilst the decision of Stewarts and Lloyds to build the giant steelworks complex at Corby in 1932-34 saw a major increase in the number and extent of local ironstone quarries to feed the towns iron and steel furnaces.

Although a valuable primary raw material, the home production of iron ore has always been closely linked to national economic and political influences. There have always been imports of ores but through wartime or periods of high economic activity the home industry has flourished.

The reverse has also been true.

In latter years, under economic pressure, most of the smaller ironworks in the East Midlands were closed together with the quarries supplying their ironstone. Despite their longevity and eventually under Nationalisation, the steelworks at Scunthorpe and Corby were effectively the only consumers of the bulk of home production. Even these consumers were forced to consider the economic viability of home production of low-grade ore against the importation of higher-grade foreign ores. When Scunthorpe converted to a new process in the early 1970’s, which relied on the higher-grade ores, the local low-grade ironstone quarries supplying Scunthorpe were closed in 1973. This left Corby as the sole consumer of low-grade ore and further rationalisation and decline followed leading eventually to a decision to close Corby steelworks. The last load of home produced ore was despatched to Corby steelworks on the 4th January 1980 bringing a once proud industry to a close, not that the mineral resources themselves have been fully worked out.

The continued development of mineral extraction techniques have now also rendered railway transport obsolete in quarries. The last standard gauge quarry railway system in Britain, at Barrington Cement Works in Cambridgeshire, was closed in 2005. Our Museum is pleased to preserve and continue to operate a range of their equipment for posterity.

Quarry locomotive “Mr D” at Barrington Quarry.

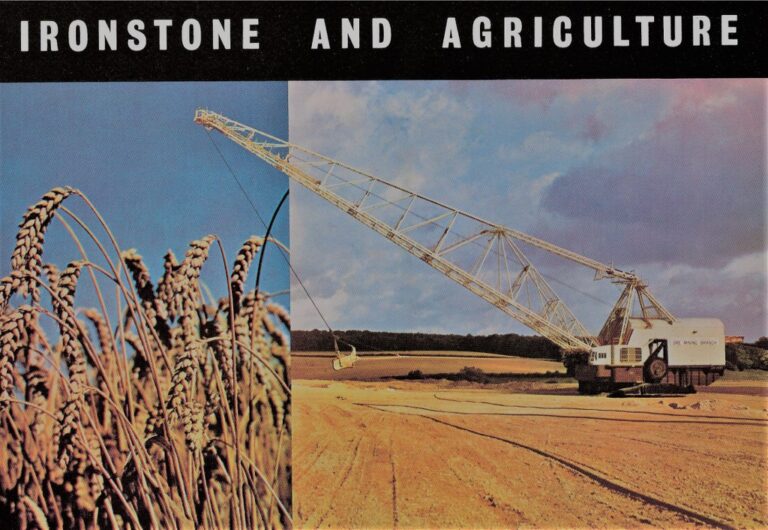

One could be forgiven for expecting that opencast quarrying would have left its indelible mark on the landscape. However it is a tribute to the past and more importantly present restoration techniques of such quarries that today it is now often difficult to identify major areas of quarried ground. Whilst some vestiges of past activity remain, these can easily be missed by the untrained eye. Some are as subtle as the changes in hedgerow planting or field layouts but equally there are also some very visible and obvious features such as “sunken fields” once you know where to look.

Restoration of workings to agriculture

While archive film and photographs exist, our Charity has gone further by preserving and demonstrating the original machinery in an authentic way on a historic site to provide the visitor with a range of experiences, which are otherwise impossible to witness.